Some 96 km south of Varanasi, the late autumn afternoon sun setting over the low-lying Vindhyas, opulent forests and the winding Son river defining Sonbhadra's rich tapestry of landscape, nothing warns you about the long night that is Bagesati. Sonbhadra is the second largest district of Uttar Pradesh, a panhandle in its southeast, sharing a border with four other states—Madhya Pra desh, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and Bihar—and Bage sati is, well, a village on all fours.

Eerie darkness looms overhead, below it's a scene straight out of Zombieland. People amble by slowly, bent, stumbling, their gazes vacant, overcome intermittently by uncontrollable trembling. Sandhya, 14, is sprawled on the floor of the courtyard outside her tenement, unmoving, lifeless, detached, just staring out with glassy eyes. "The abnormal one," her parents tell everybody. "She was such a sprightly kid," says her father Jagjivan. "But for the last six-seven years, she has been complaining of severe joint aches, numbness and muscle-twitching. Slowly she started withdrawing from everything."

Morning dispels the darkness, only to reveal more despair. It's a tiffin break at the ramshackle school building in the village. Children file out, their bodies contorted, some paralysed, teeth putrid and a few with obvious mental disorders. Their mothers, with crooked backs and bow-shaped legs, wait outside. Rakesh, 22, has convulsions from time to time. "I get tremors all over my body. My arm is slowly becoming immobile," he says. Half his body started developing deformities eight years ago.

| | | | "We found no mercury in our zone. If we provide 2,000 MW of energy to the country, minor costs have to be borne."Abhimanyu Sharma, DGM, NTPC-Shaktinagar | | | | |

|

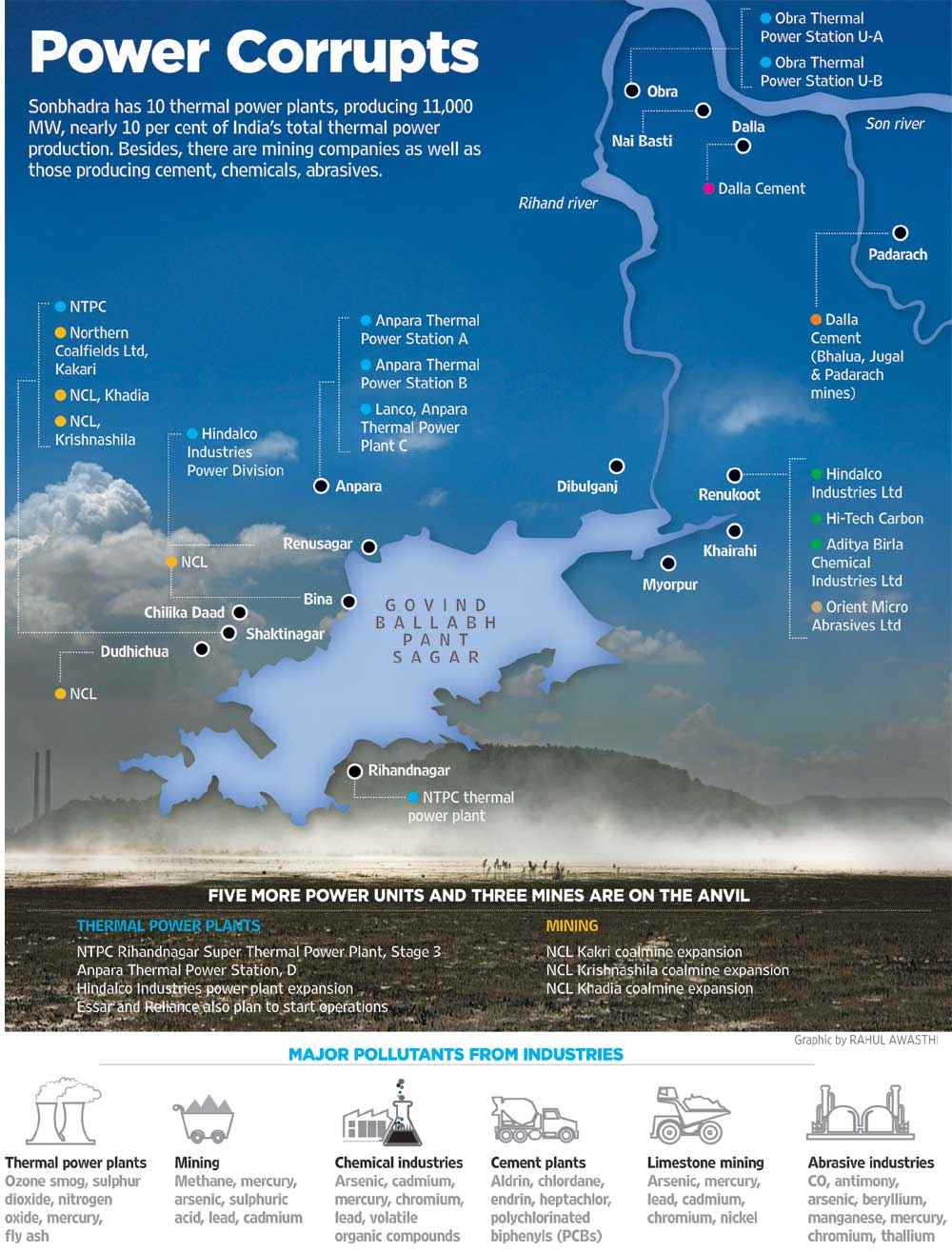

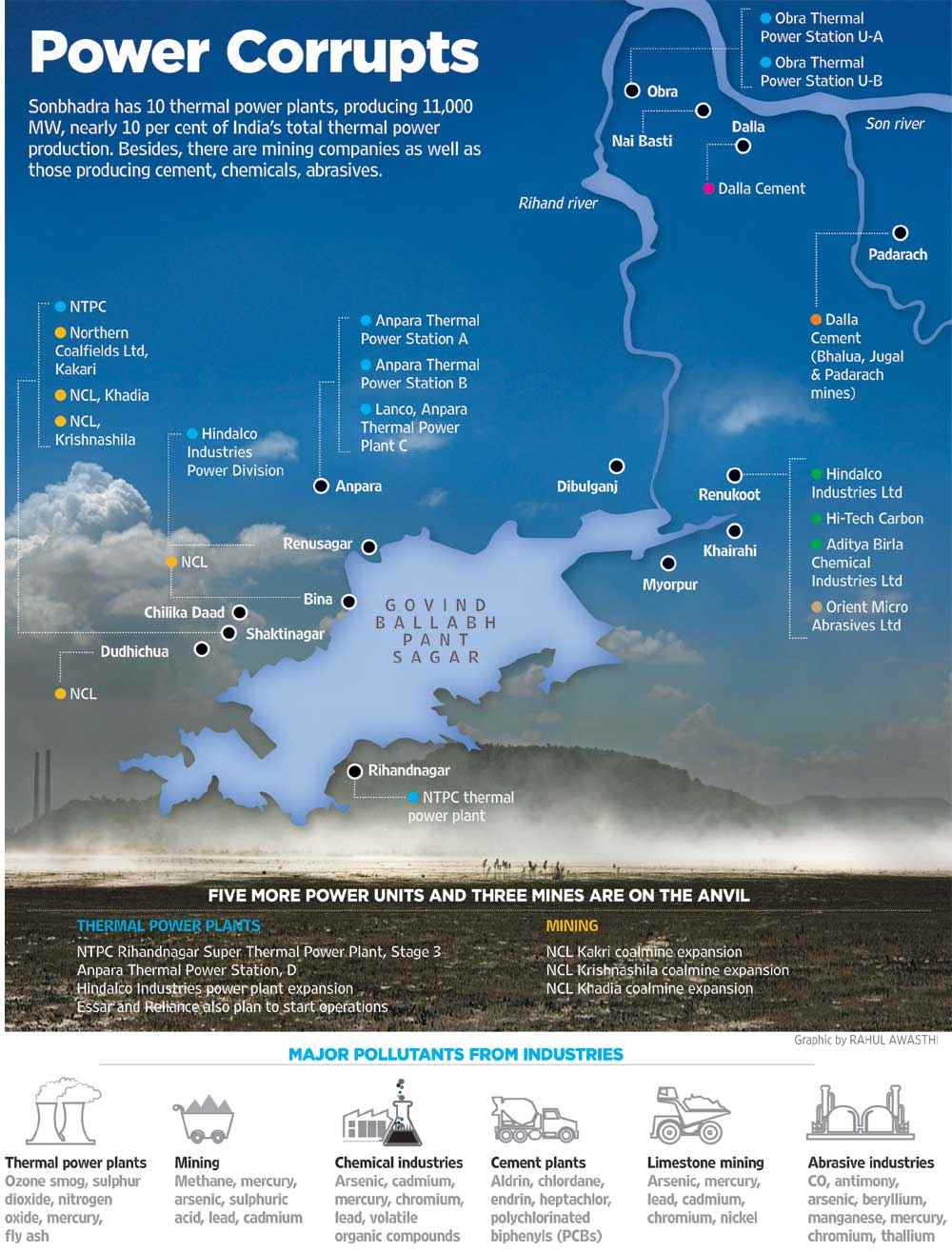

What ails Bagesati? Or indeed Kushmaha, Nai Basti, Gobardaha, Kirwani, Khairahi, Manbasa, Belvad, Pipri-Sonvani, Anpara, Dibulganj and possibly many other villages not visited. For Bagesati, the answer lies 35 km away, in the Obra thermal power plant. For the others, it lies scattered across the 7,000 square kilometres of Sonbhadra, power hub of India. Ten major power plants dot this countryside, leaving it crisscrossed with discoloured streams of blue grey, or of bright orange. Sonbhadra produces some 11,000 MW of power, nearly 10 per cent of the thermal power produced in the country.

Sonbhadra is also one of South Asia's biggest industrial zones. It is under pressure to do more, to fuel dreamsellers' grandiose plans like, the '100 smart cities' project. Like its sister city Kyoto, the ghats and galis of Varanasi are abuzz with talk of a real estate boom, of being rebooted as a swank, modern city.

There is no such hope in neighbouring Sonbhadra's air. What blows instead is an ill wind, afflicting villagers with mysterious illnesses, poisoning their land, their water, even their food. No one is spared, not the women, not the children, not the adolescents or the elderly. Cases of stillbirths, genetic disorders, menstrual irregularities and fatigue, gastrointestinal complaints, vertigo, speech, hearing and peripheral vision impairment, hyper-pigmentation and neurological problems run into thousands here, say residents and experts. Deaths too have been reported. Yogesh Kumar, a pathologist at Chilika Daad village in the coal-rich Singrauli region in southwest Sonbhadra, confirms: "We've been receiving at least 30-40 cases of infertility every month and also problems like ostoeoporosis, diabetes and skin infections. Somehow most of the blood samples show high levels of lead, mercury and arsenic."

Bindu, 18, Dibulganj

The faraway look in her eyes marks her out from the other children playing in the courtyard of a house in this village 30 km west of Renukoot. Bindu is speech-impaired and mentally challenged. She often has convulsions and her muscles twitch at night. "Who'll marry such an abnormal girl?" asks aunt Parvati. Bindu's problems began when she was five years old, with the slowing down of cognitive functions, along with discoloration of her teeth. When we ask her how she's keeping these days, she complains of severe joint aches, dizziness and painful menstrual cycles.

| | | | "We said mercury levels in water here had risen sharply, but SP leader Azam Khan said mercury's part of nature."Ruby Prasad, Ind MLA, Duddhi Block | | | | |

|

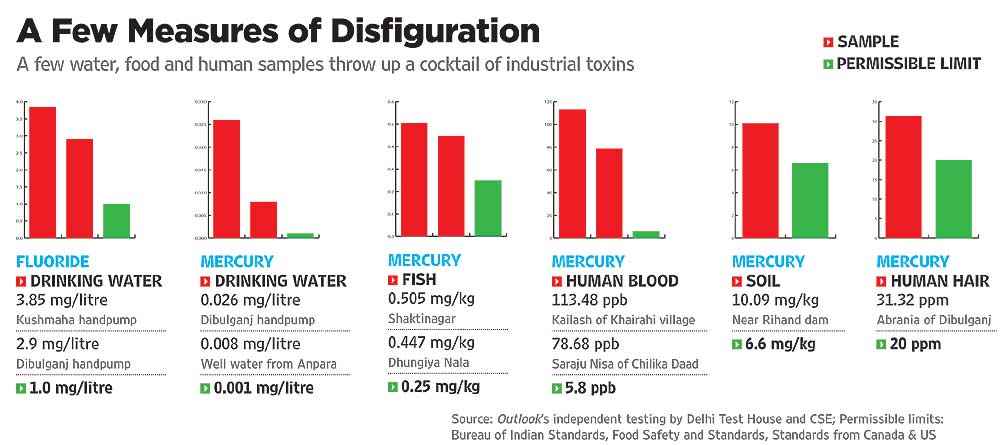

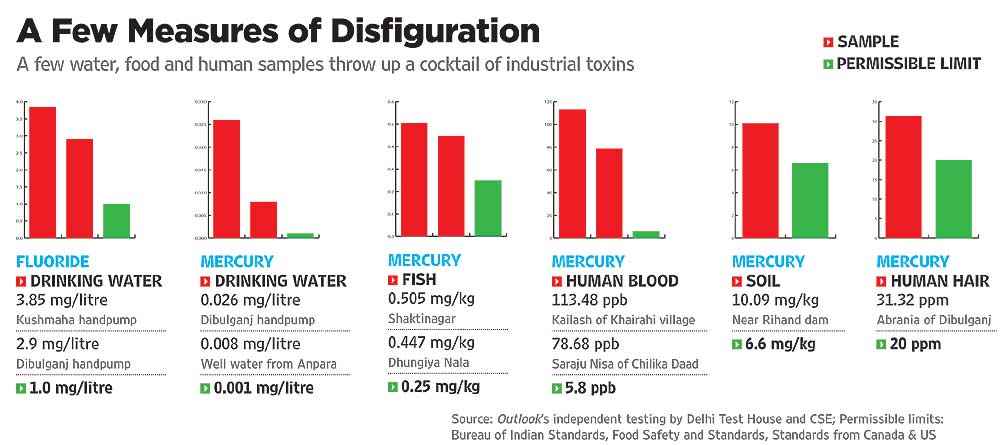

It's something that has shown up in study after study. In 2011, the Centre for Science and Environment in Delhi collected samples of water, soil, cereals and fish from the region, as also of blood, nails and hair of the residents. The results revealed frightening levels of mercury, fluoride, lead, arsenic and chromium. An unpublished study by the Central Pollution Control Board (Lucknow) in 2000-2001 concluded that the mercury poisoning problem in and around the area has definite anthropogenic origins and power plants are responsible for the pollution. The introduction of washed coal could reduce emission, but it may not be feasible under the existing infrastructure. Research studies by the People's Science Institute in Dehradun, the Hazards Centre in Delhi and the Banvasi Seva Ashram in Sonbhadra likewise pointed to high levels of mercury and fluoride in the air and water. The Indian Institute of Toxicology Research in Lucknow had, as far back as 1998, tested over 1,200 people for mercury poisoning in the area, and detected up to 500 parts per billion (ppb) of the toxin in their blood, say sources. The permissible limit is 5.8 ppb. Vegetables, fish and drinking water too were tested. But the results were never made public. Not even now, when

Outlook tried to gain access to the report.

Outlook then, with help from the Delhi Test Lab and CSE, independently tested a few samples of soil, water, fly ash, cereals and fish from the region. The results show significant levels of mercury and fluoride in some samples (see table). Surprisingly, the Bureau of Indian Standards could not specify the limits for some of the samples.

Silence seems almost like a conspiracy. Rajiv Ranjan, the doctor at a community health centre in Myorpur, 15 km from Renukoot and one of the worst affected areas, flatly denies he gets patients with any such chronic symptoms. The paediatric hospital at district headquarters Robertsganj, some 70 km north of Renukoot, admits the labs are not equipped for expensive biochemical tests. Sonbhadra's chief medical officer Dr Amarinder Singh pulls out records only of people afflicted with fluorosis. When asked about mercury or arsenic poisoning from industrial hazards, he evades the question. All he says is, "In the hilly regions, this is a common problem. So we have installed treatment plants in critical areas to supply clean water to the residents."

The apathy is all-pervading. There has as yet been no comprehensive medical survey of the region. Dr G.D. Agarwal, an environmental engineer, says significant levels of mercury can be found in wells and handpumps along the lower reaches of the Rihand reservoir, where NTPC has a thermal power plant, and can easily enter the body through water (in dissolved form as mercuric chloride or mercuric carbonate), food (methyl mercury in fish, animal food and cow milk). Most importantly, it travels through the air, almost 80 per cent of which is absorbed by the lungs, resulting in respiratory disorders and often affecting the brain. "But we need a complete medical study by qualified doctors to gauge what's really crippling this region. Our deductions are based on conjecture," he says.

Rakesh, 10, Kamlesh 6, Nai Basti

Like others in this village 15 km east of Obra, the 'disease' got to father Rajneesh Kumar first. He'd be in acute pain and wake up at night trembling, breaking into a cold sweat. Now his wife Kamla and sons Rakesh and Kamlesh are afflicted. Kamlesh's legs are scrawny, his teeth decaying and he suffers from peripheral vision impairment. Rakesh has needle-like sensations in the extremities and often gets into hysterical fits. The children have to be fed as their motor skills are impaired. "We lost our daughter to the same disease when she was just 14," says Kamla.

| | | | "The toxin's been found In critically polluted areas but within permissible limits. Coating in water? Bleaching powder."Kalika Singh, UP Pollution Control Board | | | | |

|

The authorities may be in denial but truth stares you in the eye in village after village. Reema, 12, in Chilika Daad, is weary from the continuously erupting red blotches on her body. Her brother suffers from an eczema-like condition. They talk of waste from the 'overburden' mountain of Khadia coalmine of the Northern Coalfields Limited (NCL) being washed down to the village during the rains, and NTPC's Shaktinagar plant rendering the air thick with pollutants. "When we approach NCL, they say we should speak to the NTPC authorities, and vice versa. No one wants to take responsibility," rues fellow villager Manonit. "If you stay here continuously for even seven days, you will surely complain of abdominal pain or dizziness."

Industry has been ruthless in the indiscriminate exploitation of the region. No heed has been paid to the social and environmental cost of relentless development. The story of Sonbhadra's rise on the power map of India began in 1962 with the construction of the Rihand dam and the subsequent extraction of its massive one billion tonne of coal reserve and limestone hummock. The ready availability of power lured Hindalco into setting up its aluminium plant in the same year at Renukoot at the northern end of the reservoir. Kanoria Chemicals followed suit two years later, to supply caustic soda to Hindalco. Further north, the UP State Cement Corporation set up a plant in 1967 at Dalla, near Obra, marking the first few steps in the industrialisation of the region. Over the years, big psus like NTPC as well as private players like Lanco, Jaypee Group, Aditya Birla Group et al made inroads as well, accompanied by many ancillary industries, stone-crushing units and limestone quarries.

At present, nearly two-and-a-half lakh tonnes of coal is burnt every day in Sonbhadra. Stacks over 200 metres high spew pollutants like sulphur and nitrogen oxides, fluoride and trace metals like mercury into the air, which travel almost 30-40 km, or are dumped as effluents in fly ash ponds. The contaminated water, inevitably but surreptitiously, streams into the Rihand reservoir, the lifeline of the residents of this region. Says Chandra Bhushan, deputy director general at CSE, "Most mines have poor environmental management systems. New lands are being acquired and thermal plants are being set up. There should be a cumulative impact assessment of the region before allowing more factories to come up." The blatant contravention of environmental norms was recently brought to the notice of the National Green Tribunal, which ordered the supply of potable drinking water (using reverse osmosis) to the villages. But activist Jagat Viswakarma says the lack of maintenance renders the filters ineffective.

District magistrate Dinesh Singh admits to the high levels of mercury and fluoride in some areas. But industry representatives are brazen. Says Abhimanyu Sharma, deputy general manager at NTPC, Shaktinagar, "We've found no mercury in our zone and there are no ash patches in the Rihand reservoir. Besides, if we are providing 2,000 MW of energy to the country, minor costs have to be borne." Hindalco managing director D. Bhattacharya refused to reply to our queries, ditto Lanco and the Jaypee Group. NTPC authorities in Delhi said, "We have carried out human health risk assessment studies for the residents around the Singrauli power station. No carcinogenic risk in the pollution has been observed."

Uttam, 15, Khairahi

It's hard to get Uttam to smile but he brightens up at the sound of visitors. He has been bound to this chair for five years now, his body shrinking in size, his arms paper-thin. Ask him to lift them and they tremble. His mother picks him up at bedtime and brings him back to the garden at daybreak. "Even till a couple of years back I could do some needlework, but now I feel exhausted," he admits. Uttam's father says he suffers from severe mood swings and nervousness. They pray just for one thing: that water in the Rihand reservoir, just a kilometre away, turns drinkable.

| | | | "I've spotted people with blackened teeth. Water is undrinkable too. But there has been no medical survey."Dinesh Singh, DM, Sonbhadra | | | | |

|

Pollution and water boards too have joined this game of denial. Kalika Singh, regional officer of the UP Pollution Control Board, told

Outlook, "There is no record of sickness or death due to mercury. The toxin has been found in critically polluted areas, but within permissible limits. The coating you see in water could be bleaching powder." N.K. Gupta, senior environmental engineer in the Central Pollution Control Board, claims, "All industries in the region have switched to the membrane cell method, so there are no cases related to mercury or fluoride in Sonbhadra. Industrial pollution and diseases can't be correlated." UP Jal Nigam executive engineer C.D.S. Yadav places the responsibility on health and pollution boards to assess the situation.

Politicians, of course, do what they are best at, pleading helplessness when not passing the buck on rivals. Says Chhotelal, BJP MP from Sonbhadra, "The government can't do much because it's getting a lot from the industries. There are no proper treatment facilities, x-ray machines or ambulances here, but we'll write to health minister Dr Harsh Vardhan soon." Ruby Prasad, an independent MLA from Duddhi block in Sonbhadra's south, says she raised the issue in the Vidhan Sabha twice, in 2012 and 2013. "We said that industries were disposing waste, that arsenic, fluoride and mercury levels in water had risen sharply, but Samajwadi Party leader Azam Khan claimed that mercury is part of nature, so what can we do?" When eight children from Kamridar village in Myorpur block died in 2012, the cause of the death could not be diagnosed. Ruby Prasad feels it could be toxic poisoning as the village is very close to the Rihand reservoir. "Cancer cases, kidney and liver problems have mounted, farms are diminishing and the trees look chalk-white," she laments.

Robbed of their perfect smiles Children afflicted with dental fluorosis in Gobardaha, 25 km east of Obra

Right to information queries have been a constant. Mahendra Agarwal, an RTI activist from the region, says the central and state pollution control boards never provide the reports they seek. "Nearly three lakh tonnes of coal is excavated every day, 50,000 tonnes imported and 2.5 lakh tonnes burnt. Ash is undiscerningly thrown into water, on to roads. But does anyone bother how it's impacting people's lives?" he asks. The very power the region produces to light up others' lives plunges those of its own into darkness. Even six hours of continuous power supply is too much to ask for.

After the Minamata disaster in Japan in 1956 (when waste water discharged from an industrial plant resulted in neurotoxic effects in hundreds of people), similar methyl mercury disasters were reported in Ontario, Iraq and Kodaikanal in Tamil Nadu. But the situation in Sonbhadra is daunting. The damage to its people is not physical alone, the economic status and social dimensions of the disease leave them even more vulnerable. Many have not even received compensation or disability certificates. They are condemned to live with the long-term biological effects of environmental invasion, poignant reminders of how the greed of a few becomes a curse for so many. There is no solid medical evidence to tell you what's crippling Sonbhadra, nor any desire to find out. It could be slow poisoning from methyl mercury, fluorosis, or any number of contagions in the air. Born fatalists, Sonbha dra's people see it as a blow dealt by fate. Redemption is a foreign country, death the only passport.

No comments:

Post a Comment